Ngooi joelle, LEONG ziyu

Journalism around the world

South Korea

Currently, media companies are experimenting with paid subscription models – as well as short-form video production such as TikTok – to better respond to changing audience and business trends.

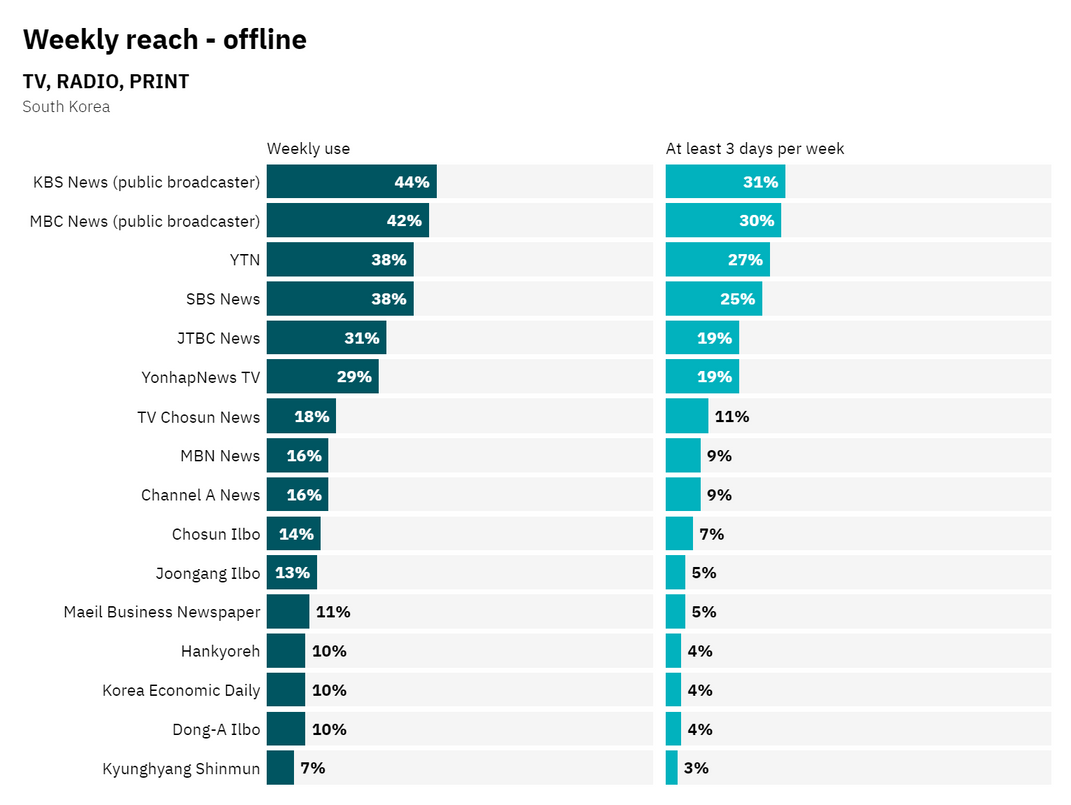

Big TV news networks including YTN, KBS, SBS, MBC, and JTBC all create custom videos for social media platforms where reporters explain breaking news in a more casual and lighthearted manner in order to capture the interest of the younger population.

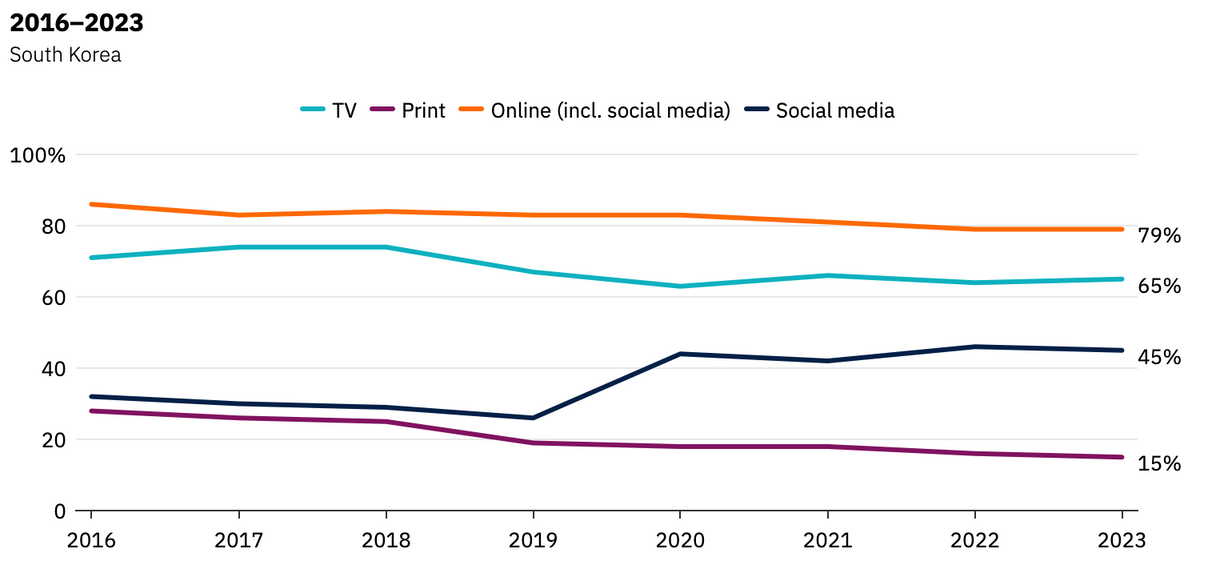

Sources of news (Lee, 2023)

A huge increase in consumption for social media since 2019 while print has consistently decreased since 2016. With the rise of online portals like Naver and Daum, print media has become less competitive.

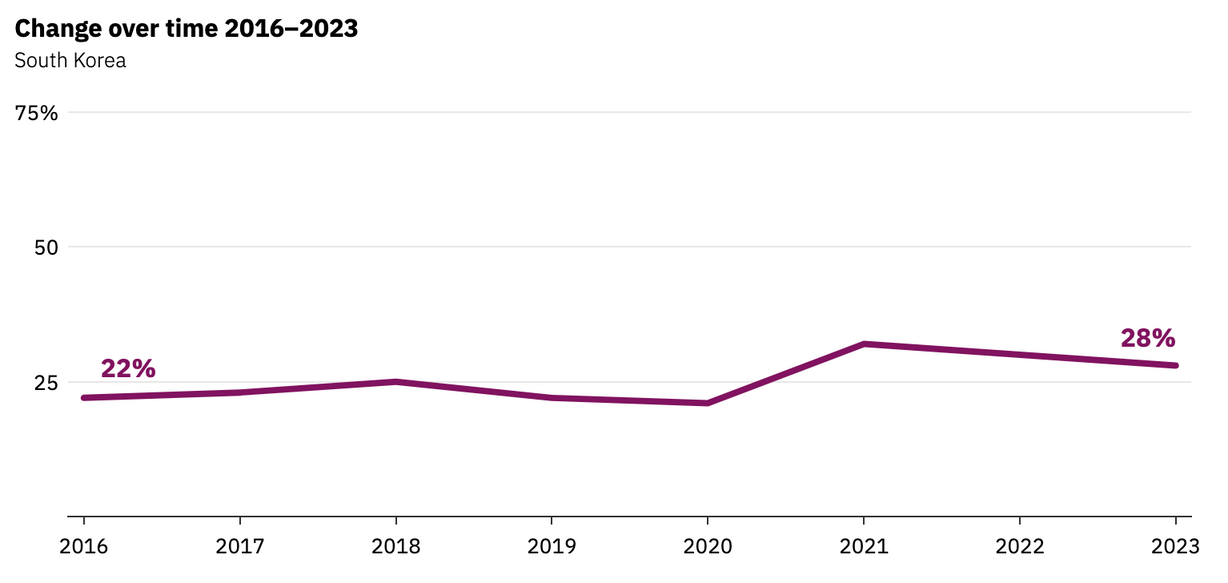

Overall trust score (Lee, 2023)

Just 28% of Korean respondents indicated that they "trust most news most of the time," reflecting the low level of trust that Koreans have in the media. MBC news is broadcasters, ranked as the most trustworthy individual news brand.

Reputable News Outlets

Press

English Language Pages

Daily

Television

Public

- Korea Broadcasting System (KBS)

- Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation (MBC)

- Education Broadcasting System (EBS)

Private

- Seoul Broadcasting System (SBS)

- Jeonju Television Corporation (JTC)

From the statistics shown above, it is clear that there has been a huge shift in the way people consume news today. With print media losing influence over time, news consumption in Korea is mostly dependent on internet portals like Naver and Daum as well as a competitive broadcast sector. The discovery and consumption of news have became much more significant because to social video platforms like YouTube.

Press Ethics Code

Freedom

Honour

and

Freedom

Responsibility

Values

Independence

Dignity

Reporting

and

Commenting

In order to correct press ethics and firmly uphold their journalistic integrity, Korean journalists organised the Korean Newspaper Editors Association, primarily comprising the editors of daily newspapers and news agencies throughout the nation. They also adopted the Press Ethics Code. The journalists have sworn to uphold the Code and meet the public's standards for quality reporting.

This Code applies to all media professionals, not only editors. Since this Code requires voluntary implementation, no reputable entity has the authority to enforce it. However, if newspapers and journalists break the Code, they will undoubtedly lose the support of the public and put their own career survival in jeopardy.

Case Study: Itaewon Crowd Crush

On the evening of October 29, 2022, several Halloween revellers crammed into a small alley in Seoul's Itaewon district, causing a fatal crowd crush. After the Halloween accident, the media was seen to have improved from their previous practises by mainly abstaining from overtly violating the privacy of the victims or airing excessively violent photographs or footage. Some local media, though, came under fire for their sensational and provocative coverage of the beginning of the mob crush. Some media outlets even received a formal warning from the Korea Press Ethics Commission for continuously airing graphic crowd crush footage, including videos of people giving CPR to the victims. Thus, this went against the value of "honour and freedom".

Press Freedom

As of 2023, South Korea has obtained a 70.83 score

and holds the 47/180 position on the RSF World Press Freedom Index.

Despite having a largely free press and an active civil society, South Korea's government continues to censor speech via harsh criminal defamation laws, broad intelligence and national security regulations.

The use of these regulations has a chilling effect which reduces public criticism towards both the government

and corporations, resulting in a false illusion of outstanding governance.

Laws & the press

The South Korean government caved in the face of harsh criticism in September 2022, cancelling modifications to a law addressing "false reporting," which raised concerns about the suppression of media freedom. The proposed changes to the Press Arbitration Law would have imposed disproportionate penalties for ambiguously defined "false and manipulated" reporting, as the special rapporteur on the right of freedom of expression pointed out.

Currently, criminal defamation laws already have a chilling effect on media reporting in South Korea, with the potential for up to seven years imprisonment and a fine. "Seeking the truth " will not be considered a valid defence if the court determines that what was said or written was not in the public interest.

This begs the question...

so how are the

Press-State Relations?

In order to look into cases of corruption involving high-ranking officials, the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials (CIO) was established in South Korea in 2021. The CIO is currently permitted by South Korean legislation to obtain phone records without first informing the subject.

One of the media organisations whose employees had their phone records accessed was TV Chosun. 34 news reporters were among the more than 70 TV Chosun employees whose phone data the CIO reportedly searched. The CIO was given a warrant in two instances involving journalists so that he could access more thorough documents.

These have led to discussions in the nation for journalists to have the right to protect their sources. In an attempt to control the press, such moves by the government can severely undermine democracy and affect overall trust in news.

Censorship

South Korea believes in one's freedom to “seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kind" except for North Korean materials. Nearly all DPRK websites are blocked throughout the nation, and broadcasts and publications are hardly ever available (Weiser, 2022).

One of the main concerns regarding press freedom in South Korea is the National Security Law (NSL), which was implemented to restrict certain forms of speech and expression, particularly those deemed to be endangering national security. NSL was enacted on December 1, 1948, just a few months after the establishment of the Republic of Korea and before the Korean War. As a result of the collapse of Imperial Japanese rule, the Korean Peninsula became unstable, with competing communist and anti-communist factions competing for power. Significant left-wing uprisings took place specifically that year at Jeju Island, Yeosu, Suncheon, and other cities. After the National Assembly passed the NSL, President Syngman Rhee and his successors have used NSL to repress members of what it calls “anti-government organizations.” (Matsuo, 2022).

Critics argue that the law's ambiguous and generic language could be used to restrict press freedom, although the enforcement and interpretation of the law have varied over time.

Under South Korean's National Security Law, it is unlawful to disseminate anything that the government considers to be North Korean "propaganda," as well as to establish, join, support, or encourage others to establish any political organisation that is thought to be a "anti-government organisation," a phrase that is ambiguously defined in law (Human Rights Watch, n.d.).

Seventy years after the Korean War, visiting and communicating with North Korea is prohibited. Access to electronic media from North Korea is blocked by an online firewall. The effect of internet censorship got little attention because printed publications were imported and added to a library maintained by South Korea's Ministry of Unification (MOU).

No new North Korean print reporting have made it to the South for three years now.

However, one may watch TV shows from North Korea in the Ministry of Unification library or on any of the more popular video-sharing websites. But nowhere can the general public get content from North Korean websites (Weiser, 2023).

Case studies of convicted journalists

Woo Jong-chang, a South Korean political commentator and journalist who belongs to the opposition camp, was found guilty of defamation on July 17 and given an eight-month prison sentence by the Seoul Northern District Criminal Court. He is currently being held for refusing to reveal the identity of a source he used in a YouTube video to suggest that Park Geun-hye's impeachment in 2017 was the result of a conspiracy. South Korea is a parliamentary democracy that generally upholds freedoms, but the country still views defamation as a crime that carries a sentence of up to seven years in prison.

In a case somewhat similar to Woo Jong-chang's, four journalists who worked for the conservative news organisation Media Watch received harsh punishments for defamation, including up to two years in prison. In December 2016, the defendants released a report accusing a newspaper of falsifying evidence that was used against the former president during her impeachment trial; she was eventually given a 25-year prison term as a result (Tzabiras, 2020).

S.K's take on its own censorship

In July 2022, South Korea’s new conservative government suddenly announced that censorship would be lifted, but half a year later nothing has changed. The ministry argued that ending censorship would help restore “ethnic homogeneity”, increase pressure on North Korea to do the same and help South Koreans to “understand” the other side. Kwon later added that citizens were now “mature” enough to be exposed to North Korean content and there were no legal hurdles to end censorship (Weiser, 2023).

N.K's take on S.K censorship

Law makers of South Korea should understand Seoul’s internet censorship itself violates not just the right to know of South Koreans, but the rights of North Koreans to send information across the border. That includes the DPRK leadership and propaganda apparatus, which has the right to share information and propaganda with South Koreans — as hard if not impossible as that is for ROK conservatives to accept (Weiser, 2022).

Key Takeaways

General Background

- Shift in ways to consume news

i.e. online>offline, web portals, social media, paid subscription models

- Overall trust in media, reputable news outlets

Journalism Ethics

- Press Ethics Code and its' importance

Press Freedom

- Largely free press but the law can be restricting and affect journalistic independence and integrity

Censorship

- National Security Law (NSL) to block North Korean news materials and journalists who broke this law

- Stance of N.K and S.K on NSL

Journalism around the world

South Korea's Media System